Nothing To Worry About (Easy Rider/Frenzy -3)

1995

video and sound projection

duration: 6 min

exhibited:

Mark Dean, City Racing, London, 1996

B.O.N.GO, Bricks & Kicks, Vienna, 1997

City Racing 1988-1998: A Partial Account, ICA, London, 2001

The Beginning of The End, Beaconsfield, London, 2010

bibliography:

Martin Herbert, ‘Mark Dean: City Racing’, Time Out, 7-14 February 1996

Burgess, Hale, Noble & Owen, City Racing: The Life & Times of an Artist-Run Gallery, Black Dog, London, ISBN 1-901033-47-3, 2002

David Curtis, A History of Artist’s Film and Video in Britain, BFI Publishing, London, ISBN 1-84457-096-7, 2007

Naomi Siderfin, ‘Mark Dean: The Beginning of The End?’, catalogue essay, 2010

Paul Bayley, interview with Mark Dean, Art & Christianity, No 67, 2011

© acknowledgements:

Easy Rider (1969) →

Frenzy (1972) →

On worrying about Nothing To Worry About: a paper for Religion & Art Forum, 18/10/21

It seems a little odd to be introducing myself as a presenter in this forum, when I was one of the people who set it up. I did so because I am interested in hearing how others experience living with questions of religion and art. I say living, because although I’ve been asking such questions myself for a long time now, I still have no answers, apart from the practice of religion, and the practice of art, sometimes in the same breath. In the languages of the Bible, Hebrew and Greek, the word for breath, ruach and pneuma respectively, is also the word that is translated as spirit.

This notion of ‘living with questions’ is taken from Rilke, who wrote in one of his Letters to a Young Poet: Do not search for answers… live the questions now, then perhaps, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer.

Speaking now as an old poet of sorts, I have found the process to be more fractious. It hasn’t felt gradual, so much as halting, and rather than not noticing it, it has been hard to stop thinking about it. I used to think this was somehow my fault, but now I just think that the relation between art and religion is a particularly difficult question, and therefore living it will be difficult.

Of course it is! Art is difficult, and religion is difficult, so together they are going to be even more difficult. But separating them is not the answer. I once gave a talk on art and religion to a group of newly arrived fine art students, as a chaplain, and one of them said to me ‘I don’t understand how you can be an artist and a priest, because art is about freedom, and religion is about doing what you’re told’.

That’s the problem with trying to deal with questions like these in any way other than through lived practice — the answers just generate more questions. Like, ‘art is about freedom’. Really? What kind of art might we be talking about here? And what kind of freedom? Not to mention what kind of religion…

So for the purposes of this presentation, I thought I would limit my enquiry to just one work, which I have been living with for most of the time I have been thinking about questions of religion and art.

I made Nothing To Worry About (Easy Rider/Frenzy -3) in the same year that I was confirmed as a Christian, and it was exhibited in my first solo show. Seen today, the religious content of the work is fairly obvious; there is a repetition of the phrase ‘I believe in God’, and later, although you haven’t heard it because I turned the sound down, there is a recitation of lines from Psalm 91: You will not fear the terror of the night, or the arrow that flies by day, or the pestilence that stalks in darkness, or the destruction that wastes at noonday… For he will command his angels concerning you to guard you in all your ways. So if I presented it to you as a work of religious art, or even an icon, perhaps you might accept it as such. However, when it was first shown, it passed as an example of 90’s young British art™, as evidenced by this Time Out review of the show by Martin Herbert, which seems to skirt around the subject of religion:

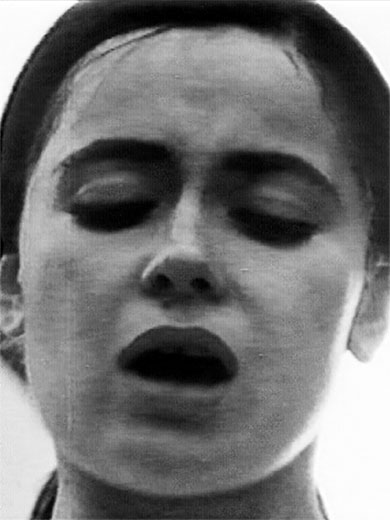

Dennis Hopper is cheering himself up. ‘There is nothing to fear but fear itself’, he quotes endlessly into a tape recorder. The scene – five seconds from Wim Wenders’ film ‘The American Friend’ – has been transferred to a video loop and is, in turn, slowed and speeded up to transform Hopper’s mood from growling determination to chipmunk optimism and back again. Mark Dean’s sharp video/sound works are concerned with reactions to life’s scary incoherence. In the next room another stammering screen plays a multi speed loop from Wenders’ film ‘Alice in the Cities’ whose male protagonist similarly murmurs ‘I’m afraid of fear’ – horror breeding horror. This is the optimism of Beckett. The scene is bracketed by symbolic frames of a bath filling and emptying down a plughole reminiscent of a scene in ‘Psycho’. And, sure enough, Hitchcock lurks downstairs. An audio excerpt from his infamously nasty film ‘Frenzy’ plays over a clip from Hopper’s ‘Easy Rider’. On screen, a woman repeatedly mouths a phrase, a protective mantra against disappointment. In this case, a sense of hope, of overcoming, glimmers through. It’s the strongest piece here, an impressively poetic, radical reshaping of the source material. As the characters enact their reassurance rituals, we have to wonder whether it’s really for the best. Perhaps, like Dean’s judicious editing, they are merely blocking out the sight of the bigger picture. (Martin Herbert, ‘Mark Dean: City Racing’, Time Out, 7-14 February 1996)

For tonight’s presentation I deliberately turned the sound down before the central section of this work, which contains the audio taken from the rape and murder scene in Frenzy. I have come to understand that I need to be careful how I show this work, because it seems to affect different people in different ways. The year after it was first exhibited at City Racing in London, it was shown at Brick and Kicks in Vienna, and again in London in a survey show at the ICA in 2001, and I’m not aware of anyone objecting to it. But about ten years ago I presented it to a group of postgraduate students in Oxford, who identified as Christians. They were not art students, but they were interested in the arts, and had invited me to talk to them about my work as an artist and newly ordained priest. After the screening one of them physically wagged their finger at me and said I should turn to Christ. They said they did not want to see things like that, and they didn’t want their children to see them either, at which their partner nodded in agreement. I could have argued that, firstly, I had already turned to Christ, thank you very much; secondly, all they had seen on screen was a person reciting the first line of the Creed; and thirdly, their children were not in the audience, and I wasn’t planning to invade their home and expose them to my work.

But I didn’t argue, because I realised that the context of the work had shifted since I had made it, and I needed to try to understand how. I thought maybe it was because they were a religious audience, more than an art audience, although I should also say that not everyone present took the same view of the work as this couple. It is an unfortunate fact that a small number of Christians claim to speak on behalf of all Christians, of Christ even, and they tend to be the most vocal, and judgemental.

But a year or so later I showed the same work to another group of postgraduate students, who were studying Fine Art, and who had not declared any religious affiliation. One of these got very angry with me for showing this work, saying that it was irresponsible to have done so, as it was triggering. I can understand this, which is why I am more careful where and how I show it these days.

I think there are three problems with this work (by problems I mean questions, not necessarily faults). Firstly, and obviously, it references rape, which, despite its prevalence as a subject in art history, is problematic by definition, and perhaps has become a more sensitive issue since this work was made. Am I qualified to make art work about rape? I hope my work was not insensitive to the feelings around the subject, although I recognise that they are not easy.

The second problem is that the protagonist in the original film footage is female. Am I qualified to make such an appropriation? Conscious of this question, I lowered the pitch of the audio taken from the rape scene in Frenzy in order to masculinise the subject. The relationship of the film’s image to the film’s sound is therefore ambiguous, and this ambiguity may also be present in the relationship of the protagonist to the author of the work. I had learned to distance myself from my work in this way after making my first video, which used home movie footage of myself as a child. This work happened to get written about in the national press, where the reviewers referenced sexual abuse. Although I had not spoken about it publicly, it was true that I had been sexually abused as a child, and the work was dealing with this at some level, but the person who abused me was not a member of my family, and in any case, the work was not intended to be read as simply autobiographical. This was one reason I began using footage from other people’s films, but when I appropriated representations of female characters, which I do for a complexity of reasons, I was aware that there was the potential for the work to be read as objectifying, and this concerned me, although not enough to stop me making the work – art is about freedom, after all.

I was eventually reassured when Rachel Withers’ wrote in ArtForum, in reference to a text for a retrospective of my work: Briefly alluded to is the artist’s childhood experience of rape, a shocking detail that suggests a searing therapeutic dimension in certain works. Goin’ Back (The Birds/The Byrds x 32 + 1), 1997, manipulates Hitchcock footage of a bloodied, collapsed Tippi Hedren, shifting her back and forth from wide-eyed dreamy repose to terror as she fights off Hitchcock’s attacking lens. On the sound track a repeated line from a pretty Byrds tune sings of “going back,” a paradoxically soothing reference to, in Dean’s words, “the recovery of traumatic memory.” Hedren becomes a surrogate for the artist in a nuanced and moving moment of crossgender identification. (Rachel Withers, ‘Mark Dean’, Artforum, April 2011)

I am aware that this too might provoke finger-wagging, as some Christians claim that God created life on a male and female binary, and that this ‘naturally’ determines the way we should live today. To my mind this seems a fundamentally pagan idea, rather than Christian. I refer to the words of St Paul in his letter to the Galatians, which say: there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus. (Galatians 3.28)

This brings me to the third problem with this work, which is its religious content. What constitutes this content, and who decides? I suppose if, like tonight, I had only shown the first part of the work to the finger-wagging Christians, they would not have objected. I trust that the statement ‘I believe in God’ would have been acceptable to them. So it seems that the other part of the work, the audio representation of rape, was somehow considered irreligious. But in what way? Was I glorifying sexual violence? Even the person who felt triggered by the work did not accuse me of this. So was it a more aesthetic kind of sensitivity? Some people view both art and religion as abstract ideals — art as spirituality, and spirituality as ethereality. But I suspect that this was not the case here; as culturally sophisticated postgraduate students they would not have been shocked by the idea of rape as a subject in art, and as committed Christians, they would presumably have agreed that religion is about dealing with real life.

I think that there was a deeper issue, with the narrative content of the work, whereby the protagonist calls on God to help her, but is killed nonetheless. Her belief in God continues, and so to those who have ears to hear perhaps, a sense of hope, of overcoming, glimmers through. But is this enough?

There is a story in Luke’s gospel of a time when Jesus preached in his own home town, and: All spoke well of him and were amazed at the gracious words that came from his mouth…. And he said, ‘Truly I tell you, no prophet is accepted in the prophet’s home town. But the truth is, there were many widows in Israel in the time of Elijah, when the heaven was shut up for three years and six months, and there was a severe famine over all the land; yet Elijah was sent to none of them except to a widow at Zarephath in Sidon. There were also many lepers in Israel in the time of the prophet Elisha, and none of them was cleansed except Naaman the Syrian.’ When they heard this, all in the synagogue were filled with rage. They got up, drove him out of the town, and led him to the brow of the hill on which their town was built, so that they might hurl him off the cliff. But he passed through the midst of them and went on his way. (Luke 4.16-30)

The usual interpretation of this story is that the people became angry because Jesus was suggesting that God cared for Gentiles at least as much as for Jewish people. But I’m not convinced that would account for them going from speaking well of him, to trying to murder him. I suspect that what really drove people mad was being reminded that while God can save and heal, people still get sick and die. Or get raped and murdered. Are we only willing to believe and trust in God so long as such things will not happen to us? Of course, we don’t care to admit that our faith is so conditional. And neither do we dare to admit we are angry at God for allowing such things to happen. But we have to blame someone. So shoot the messenger.

I said that art is difficult, and religion is difficult, but the truth is, life is difficult. Sometimes very difficult, scarily incoherent even, and so yes, we do need our reassurance rituals, which sometimes take the form of art, and sometimes religion, and maybe in that sense at least, they are not so far apart.